Kôan Boxes, private collection, Woodstock, NY

There, a desert. There, an emerald sea listing atop a coral underworld. There, the darkest moment of a forest. There, a rocky outcropping, the sound of one’s heartbeat against the wind. All these things, and none of them, are contained in Fodor’s riddles.

—Zane Fischer, Simple Complication, Koan Boxes at Lannan (scroll down for complete review)

Kôan Boxes

Kôan Box Hansa Yellow/Permanent Green/White, 2019-23 (LFKB202311)

oil, alkyd resin, wax & 23kt yellow gold on wood cigar box w/ embedded items

10.5 x 8.25 x 2 inches / 26.67 x 21 x 5 cm

$4,200.

Kôan Box Cairn 20 Pink/Orange/Ochre, 2019-22 (LFKB202202)

oil, alkyd resin, wax & 12kt yellow gold on wood cigar box w/ embedded items

10.5 x 8.25 x 2 inches / 26.67 x 21 x 5 cm

$4,200.

Kôan Box Green/Pale Blue, 2020-23 (LFKB202310)

oil, alkyd resin, wax & 12kt white gold on wood cigar box w/ embedded items

10.5 x 8.25 x 2 inches / 26.67 x 21 x 5 cm

$4,200.

Kôan Box Trace Pale Green/Yellow Green, 2018-23 (LFKB202305)

oil, alkyd resin, wax & 12kt white gold on wood cigar box w/ embedded items

10.5 x 8.25 x 2 inches / 26.67 x 21 x 5 cm

$4,200.

Kôan Box Blue-Green/Blue-Violet Mist, 2020-23 (LFKB202303)

oil, alkyd resin, wax & 12kt white gold on wood cigar box w/ embedded items

10.5 x 8.25 x 2 inches / 26.67 x 21 x 5 cm

SOLD

Kôan Box Pale-Green/Yellow-Green Mist, 2020-23 (LFKB202304)

oil, alkyd resin, wax & 12kt white gold on wood cigar box w/ embedded items

10.5 x 8.25 x 2 inches / 26.67 x 21 x 5 cm

$4,200.

Kôan Box Trace Permanent Green/Sap Green, 2019-23 (LFKB202306)

oil, alkyd resin, wax & 21kt moon gold on wood cigar box w/ embedded items

10.5 x 8.25 x 2 inches / 26.67 x 21 x 5 cm

$4,200.

Kôan Box Trace Titanium White/Orange/Ochre, 2019-23 (LFKB202312)

oil, alkyd resin, wax & 12kt yellow gold on wood cigar box w/ embedded items

10.5 x 8.25 x 2 inches / 26.67 x 21 x 5 cm

$4,200.

Kôan Box Trace Ultramarine Blue-Violet/Blue-Violet, 2019-23 (LFKB202307)

oil, alkyd resin, wax & 21kt moon gold on wood cigar box w/ embedded items

10.5 x 8.25 x 2 inches / 26.67 x 21 x 5 cm

SOLD

Kôan Box Trace Deep Maroon/Deep Red, 2019-23 (LFKB202308)

oil, alkyd resin, wax & 12kt yellow gold on wood cigar box w/ embedded items (LFKB202024)

10.5 x 8.25 x 2 inches / 26.67 x 21 x 5 cm

$4,200.

Kôan Box Ulltramarine Blue/Green/Grey/White, 2015-16 (LFKB201608)

oil, alkyd resin, wax & 12kt yellow gold on wood cigar box w/ embedded items (LFKB201608)

10.5 x 8.25 x 2 inches / 26.67 x 21 x 5 cm

SOLD

Kôan Box Cairn 21 Red/Orange/Maroon, 2019-23 (LFKB202301)

oil, alkyd resin, wax & 23kt yellow gold on wood cigar box w/ embedded items

10.5 x 8.25 x 2 inches / 26.67 x 21 x 5 cm

SOLD

Koan Box Alizarin/Red-Violet/Paynes Grey, 2018-20 (LFKB202025)

oil, alkyd resin, wax & 23kt yellow gold on wood cigar box w/ embedded items

10.5 x 8.25 x 2 inches / 26.67 x 21 x 5 cm

$4,200.

Kôan Box Cairn 23 Green/Pale-Green, 2019-23 (LFKB202309)

oil, alkyd resin, wax & 231kt moon gold on wood cigar box w/ embedded items

10.5 x 8.25 x 2 inches / 26.67 x 21 x 5 cm

SOLD

Kôan Box Cairn XII, 2017-20 (LFKB202011)

oil, alkyd resin, wax & 12kt white gold on wood cigar box w/ embedded items

10.5 x 8.25 x 2 inches / 26.67 x 21 x 5 cm

$4,200.

If you would like to have real-time information about the work please call or send me a Text Message. If I cannot answer when you call, please leave a message and I will return the call shortly. I would love to have a conversation about the work, or set an appointment with any of my dealers using FaceTime or Zoom.

Kôan Boxes, Lannan Foundation, January - March, 2009

Review:

Lawrence Fodor knows a strange but useful secret…

It’s not a very well hidden secret: it’s more of a wisdom that anyone can grasp from a sudden intuition or a moment of derailed thought that opens a new door. Almost like a kôan.

In fact, Fodor’s secret is that there is no difference between a kôan—the quirky, traditional dialogue structure of Zen practice—and a painting. The best contemporary paintings elude the rational analysis that critics and curators and the like insist on leveling. Instead, these paintings persist through intuition, through disruption of the expected, through playfulness, through the artist’s legerdemain, just as kôans have been doing for well over 1,000 years.

Fodor’s current exhibition, not so clandestinely called, Kôan Boxes, is on view in the small, sparse gallery of the Lannan Foundation. With its lively proportions, dark earthen floor, perfectly plastered walls and subtle lighting, the gallery is a room in which a used diaper would look good. Therefore, it is worth approaching anything in there with a certain amount of suspicion and attention. Because the Kôan Boxes are so much smaller than Fodor’s more familiar, large-scale paintings, because the title and the fact the exhibition illuminate Santa Fe’s often hypocritical “showy Buddhist” tendencies: and because globby, not necessarily thoughtful painting is all the rage, one might well expect to be underwhelmed by the exhibition in advance of actually seeing the work.

If you meet Buddha on the road, kill him. So goes one of the more famous and catchy kôans, attributed to Línjì Yìxuán. The idea, which we are likely in full violation by discussing it here, is to destroy preconceptions, to be present and experiential without getting all confused, by well, thought.

Fodor’s own signature pieces are quite serious and deliberate. These smaller works are, in fact, dialogues with his larger pieces, accidental accompaniments that begin as a by-product of his studio practice. The details would only encourage preconception, and the contrapuntal nature of the work is enough to merit a few moments of meditation.

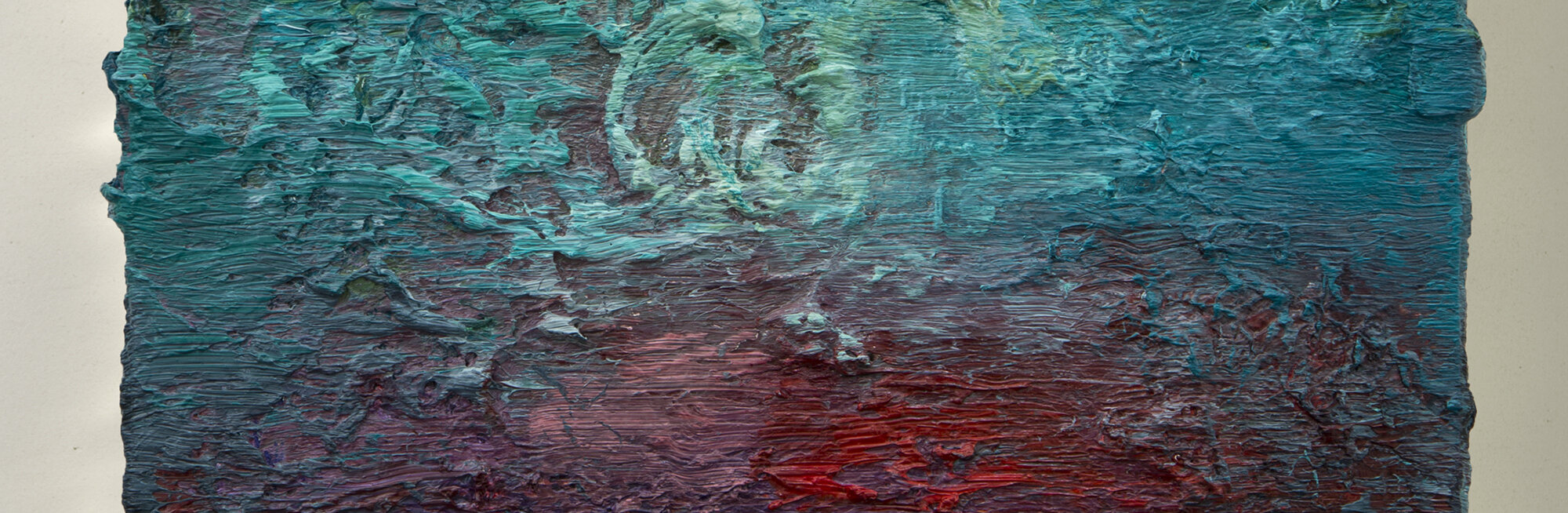

There is enough paint on the surface to build up an edge that overhangs the structure of the “box” on which it sits. The effect is of a plane being propelled out in space, hanging tentatively in the air. The manifold surfaces have been scraped, dragged, blobbed, smudged, dripped and worked. The result is more one of depth than of texture, serving to inspire the illusion that plane is also portal. The deep frames of each box are finished in gold or silver leaf and the reflection generates a radiating halo effect around each work and only magnifies the total effect of the mysterious mirage.

Through daring or dumb luck, a series of alarming color choices conspire to encourage Kôan Boxes to spasm with geography. There, a desert. There, an emerald sea listing atop a coral underworld. There, the darkest moment of a forest. There, a rocky outcropping, the sound of one’s heartbeat against the wind. All these things, and none of them, are contained in Fodor’s riddles.

Mostly though, in reminding us that a painting is simply a matter of ill-behaved poetry, of provocative and sudden philosophy, Fodor reinforces the validity of all responses. There is no right answer to a kôan, just as there is no proper response to a painting. But just as predictability is ineffective in the manufacture of artwork, it is tiresome as a response.

A corollary to the kô-an is the catalogue of responses to the question, “What is the Buddha?” One famous answer, attributed to Yúnmén Wényan: dried dung.

So what if Fodor is pulling the wool over our eyes? What if these “kôan paintings” are just follies that look good in a particularly good-looking room? Well, that would be a pretty good kôan, too.

But don’t think about it too much.

—Zane Fischer, Simple Complication, Koan Boxes at Lannan

Kôan Boxes and paintings in progress, LA studio, July, 2019

Kôan Boxes in the LA studio, (private collection)

Essay in the Lannan Foundation published catalogue:

A Gift: the Painted Boxes of Lawrence Fodor

Before Pandora became curious about the contents of the box, she was attracted to it.

Lawrence Fodor creates large scale paintings and small, intimate painted boxes at the same time. Both attract the viewer with their subtle modulations of color, layered coats of paint, and dripping, frosting-like texture. The paintings, however, satisfy a viewer’s curiosity with their surface. Close inspection reveals all the aforementioned. The boxes—equally attractive on the surface—tease the viewer with the prospect of hidden secrets. Fodor sometimes collects a variety of materials related to his daily life and sometimes to the life of the recipient of the box and places all of it inside. Once sealed, the art work becomes a time capsule filled with the ordinary, the personal, and the random. Other boxes remain empty but when held and shaken they still provoke curiosity because of the memory of the boxes filled with secrets.

The boxes, usually wooden cigar boxes, are literally made at the same time as the paintings because Fodor places them at the bottom of his painting to collect the drips and daps. Slowly the boxes become covered with paint from multiple works. They are the remains of the day. After the boxes have a sufficient amount of paint, the artist sometimes works with it in a more intentional manner applying the paint on the surface as if it were one of his paintings. Some boxes, however, are finished without this attention. The sides of the boxes--they are approximately two inches in depth--are sometimes gilded gold or silver. Sometimes they are left “raw.” The small clasp that locks the box remains apparent.

The skin of paint on the surface of the box is formed intuitively and sometimes arbitrarily. Fodor considers the boxes as “meditations on color: considerations of color contrast, relationship, and, at times, paradox.” Because of this idea of paradox, the painter refers to the boxes as kôan, which is a paradoxical statement used in Zen Buddhism to provoke enlightenment and further questioning. Fodor wrote that the boxes offer the viewer the possibility to consider “the infinite variety, possibility, and responses to color.” The paradox at the heart of the boxes is that the color can be understood in multiple ways: intellectual, emotional, intuitive and/or cultural. As a result, the intentions of the artist become secondary to the viewer’s understanding of the piece based upon their prior knowledge and experience.

Although sculpture as much as painting, Fodor intends the works to go on the wall. The backs remain in their original condition. The pieces can be display individually or in groups, but such group arrangements are composed after the works have been created. For Fodor the painted containers are highly personal works not meant primarily for the gallery, museum or other art–settings. Many have been presented to friends and family as a gift to honor goodwill, emotional connections, and valued memories. Their scale allows for intimacy and the form conveys the idea of a gift. But at the same time that Fodor offers this gift of intimacy, he also denies it. Let me explain.

Fodor began collecting cigar boxes when he was a child. They became valued for their ability to lend organization, order to his many valued possessions. Paints, pencils, cars, badges--the stuff of boys-- became the secrets and the memories that resided in the boxes. The desire to organize and hold on to these things in an aesthetic, boy-sized container speaks to a need to create a place more rationale, more controlled than the world at large. It also perhaps tells of a child that doubted his ability to hold on to the good in face of the bad, who needed an external world of things to remind him of what he valued, what he hoped to be, of the relationships that shaped his world. But despite all that he communicated in his box collection, they remained largely his alone; things transformed and infused with the secrets of his life.

As a young adult, Fodor revisited the idea of the box with secret contents in an enlarged form. During the process of remodeling and then selling a house he drew and painted scenes on the walls that were covered over or hidden. Like archeological remains that were intentionally buried so that later civilizations would find them, Fodor’s “house art” is an artifact for later discovery and appreciation. But, the appreciation of the art will be based on incomplete information. The works will still be aesthetically compelling to some degree (it will all depend on what remains), however, the artist, his intentions, and his context will only be known in part, if at all.

Fodor’s boxes brimming with the stuff of life, or completely empty, remain sealed and only partially known. The surface of the box, both arbitrarily and intentionally formed, never completely conveys the artist’s conscious intent. A gift of intimacy, of knowing / a gift of denied intimacy, of not knowing.

In the twentieth century many artists have explored this type of art that delves into the psychology of collecting, the need to maintain secrets and the desire to provoke the imagination. Marcel Duchamp, the master of such art, created With Hidden Noise, 1916, a Readymade sculpture that consists of two copper plates and four long bolts that sandwich a ball of twine. Duchamp’s friend and patron, Walter Arensberg, inserted an object into the ball of twine, sealed it with the plates and bolts, and never told anyone what he placed inside. When held, the sculpture becomes interactive. The viewer becomes an active creator of the art, imagining what might be inside. Like a child with a wrapped Christmas present, the viewer enjoys the sealed sculpture because it allows their imagination, fueled with anticipation, to run wild. Duchamp repeated this trick several times in his art, making sealed time capsules that contain dust, air, and other debris that represent the passing of time, the brevity of life. Like Pandora’s Box, however, Duchamp’s closed works of art also offer the hope for life after death, hope for imagination and creativity rewarded, and hope for insight into the mind of the artist.

Joseph Cornell used cigar boxes and other types of small boxes as the structure to house and present his art. A compulsive collector of ephemera, Cornell created elaborate alternative worlds that paralleled his lived reality but enhanced it by making it more imaginative and aesthetic. For example, the artist by his own admission was a rather obsessive fan of movie stars, ballerinas and opera singers. In the hands of someone less gifted, his obsessions would have been the stuff of tabloid headlines and restraining orders, but Cornell contained his desires and turned them into aesthetic rifts that speak of an intense desire for connection and an equally intense desire to avoid connection. This universal human struggle allows his art to transcend the individual to become symbols for an imagined world where our desires are fulfilled by creative acts.

Another artist who expanded the vocabulary of the art box is Jasper Johns who in 1955 created Target with Four Faces. This sculpture/painting presents a colorful, painted bulls-eye target with four half-faces made of plaster that rest on top of the painting. These four masks are in wood boxes that have a hinged lid that can close and open. Scholars have offered much speculation about the meaning of this work. What most agree on is this enigmatic work wishes to convey both exceedingly clear information (the target) and rather opaque information (the half faces in boxes). The juxtaposition of these two symbols evidences a desire to speak clearly and at the same time to remain partially obscure. Art is a perfect vehicle for secrets half told and artists have longed buried their longings, fantasies and unrecorded deeds in their art. For Johns the lidded box that can be opened or closed at the discretion of the viewer became the most apt metaphor for his life that was filled with half-spoken truths known by some and not by others.

Fodor’s painted boxes converse with all of the work by the artists aforementioned. Duchamp’s wit, Cornell’s sublimation, and Johns’ personal secrets, are woven into his art that asks for our curiosity and participation. Unlike their work, however, the outside of Fodor’s boxes are equally attractive—if not more so—than the imagined contents. Like small treasure chests, the works are embellished with succulent paint and precious metal. It is as if the contents of the box have been aggrandized by the box itself. Like a simple letter opener in a Tiffany box, it is hard to know which present is more enticing.

—Timothy Rodgers Ph.D. Sybil Harrington Director and CEO , Phoenix Art Museum

from the catalogue for Koan Boxes at Lannan Foundation, 2009, Twin Palms Press

The Kôan Boxes

My work is driven by the sum experiences of a highly personal journey. I have been fortunate to travel the world multiple times, live in Kathmandu, Nepal for a year, delve into diverse religions including Buddhism and Zen, train in Transcendental Meditation and study art history while pursuing a career in painting. Leaving indelible marks on my psyche, these accumulated encounters continue to influence my conceptual concerns and studio practice annealed by a heightened awareness for and gratitude of the moment.

I have collected cigar boxes since my youth, as repositories for the treasures of my childhood. They entered my studio practice sometimes in the mid-90’s, but as time capsules filled with items relating to a friend, that I would paint on, seal and gift to that friend with the intention of being opened in 25 or 30 years. Their function and use in the studio shifted around 2004, and the term kôan came to mind.

A kôan is a story, anecdote or statement generally posed as a question in Zen practice serving to broaden insight into Buddhist teachings, provoke the “great doubt,” develop a higher awareness of the moment and test the student’s understanding and progress in Zen. A kôan is sometimes a paradoxical question, steeped in contradiction with no correct answer or response, other times there is a specific answer upon which a student is required to memorize and meditate. A kôan cannot be understood by logic, cannot be transmitted with words, cannot be explained in writing nor cannot be measured by reason. A kôan generally encourages intuitive meditation on the statement itself and practiced with the aim of gaining insight into the “non-duality of subject and object.” This term seemed to perfectly describe the journey each cigar box takes, their intention, premise and ultimate objective.”

The Kôan Boxes are weighted in paradox and contradiction: they begin as utilitarian objects, palettes for the larger paintings, that eventually evolve into works of art through random, intuitive and unintentional accumulations of paint; filled with found and made items and objects, they are sealed time capsules that will never be opened; they are a culmination of painting in the moment, but also filled with collected memory and artifacts from the past; they embody the non-duality of the dual realties of my differing work environments; they are gilded on their sides, in direct opposition to traditional western framing, which functions to intentionally cast reflections on the wall that anchors the box while simultaneously becoming a kind of “halo,” placing them in an ethereal realm with the illusion of hovering in front of the wall.

Beyond their intention and the multiple layers of paradox, the Kôan Boxes, in the end, become intimate objects on which to meditate, ponder, discover and perhaps ultimately impart an awareness and integration of the moment as we experience art.

—Lawrence Fodor, Koan Boxes, March 2020

Kôan Box Cairn IX, 2017-20, oil, alkyd resin, wax & 12kt white gold on wood cigar box w/ embedded items, 10.5 x 8.25 x 2 inches / 26.67 x 21 x 5 cm

Kôan Boxes in various states and process, LA studio, March 2020

Kôan Box Sap Green/Blue-Green/Alizarin, detail